Family members have asked Ana Valeria Mayén Lainez, M.D., a neonatologist from El Salvador, about the worst thing she’s seen in her work. She didn’t used to have an answer.

But Mayén Lainez, as a Technical Advisor to the USAID-funded, URC-led ASSIST Project in El Salvador, was on the frontline as Zika rapidly spread through Latin America and the Caribbean in 2016. She saw mothers with babies with severe developmental delays caused by microcephaly. There was little that Mayén could do to help them. This is the worst thing she’s ever seen.

We have made progress in Zika since then, said Mayén Lainez. She often thinks of Hippocrates, who said: “Cure sometimes, treat often, comfort always.” That’s where we are with Zika now, she said.

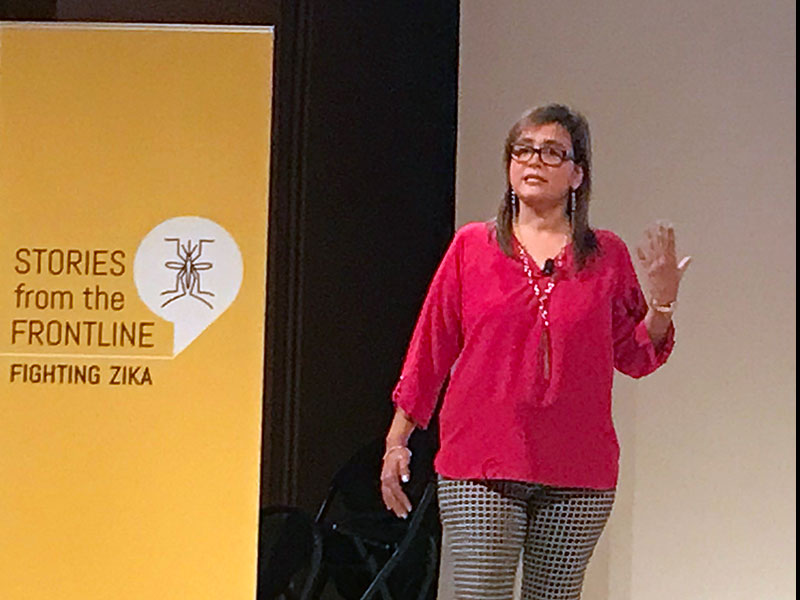

On Aug. 20, Mayén Lainez joined five other public health workers and scientists, invited by the USAID Bureau of Global Health and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, to share their personal and professional stories about the Zika outbreak during at a public event, “Stories from the Frontline – Fighting Zika.”

The session, held at the Museum of Natural History, featured representatives from the Red Cross, NASA, the U.S. Army, USAID, a Christian non-profit, and other organizations.

From Nuisance to Severe Threat

The Zika virus wasn’t always as dangerous to humans as it is today, according to the World Health Organization. When Zika was first detected in people in 1952 in Uganda and Tanzania, it caused only mild, flu-like symptoms.

But mutations, the rise of global travel and shipping, and the Aedes aegypti mosquito – which thrives in urban areas and bites during the day – allowed a new, more harmful version of the Zika virus to reach northeastern Brazil in late 2014 and spread across the country in 2015.

Brazilians had little immunity to Zika, which led to an outbreak responsible for 54 cases of microcephaly – plus other neurological disorders – in newborns between August and October 2015. More recently, scientists discovered the virus also is sexually transmitted.

Worldwide, around 3,900 babies have congenital Zika syndrome, but no one knows how many have been exposed to the virus, Mayén Lainez said.

Zika has no cure, but the U.S. Army is conducting human trials for a vaccine, said Yvonne Linton, U.S. Army, Science Director for the Walter Reed Biosytematics Unit and one of the participants in the Aug. 20 event.