In June 2020, Mr. Lukungu Sospetari, 84, visited Busesa Health Center IV in Bugweri District, Uganda, complaining of a cough, general weakness, and weight loss – all symptoms of a tuberculosis (TB) infection. During the visit he was diagnosed with TB.

Sospetari was immediately started on a six-month course of TB treatment. Once completed, Sospetari failed to return to Busesa Health Center IV to provide a sputum sample to confirm he had been cured from TB. Instead, he was followed up at home by Tadeo Baziwo, a sub-county health worker, to collect his final sputum sample for testing. Lukungu received a negative sputum TB test result confirming that he had been cured from TB.

Connecting with Lost to Follow-Up Patients

A patient on TB treatment is classified as ‘cured’ after completing six months of TB treatment and after testing negative for TB. A positive test result after six months of treatment can point to several challenges, including lack of treatment adherence and TB drug resistance.

However, during a district TB quality improvement (QI) collaborative meeting facilitated by the USAID RHITES-EC Project, Amina Byobon, the Bugweri district TB and leprosy supervisor, learned that patients rarely return to health facilities for a TB test after treatment as instructed.

To address this challenge, Byobon and her colleagues agreed that patients who fail to return for their six-month TB testing would be followed-up in the community by sub-county health workers for sputum sample collection to confirm they are cured.

Sub-county health workers are community members trained by RHITES-EC to support district TB activities at the community level. These health workers link people to health facilities and patients to TB diagnosis and treatment. Their work includes tracing TB contacts, conducting door-to-door TB screening, delivering TB medication to remote patients, visiting patients lost to follow-up, and mobilizing communities for TB outreach.

Byobon supervises Bugweri District’s sub-county health workers in their efforts to trace and collect sputum samples from TB patients without a registered six-month TB test.

Community Outreach for TB Diagnosis and Treatment

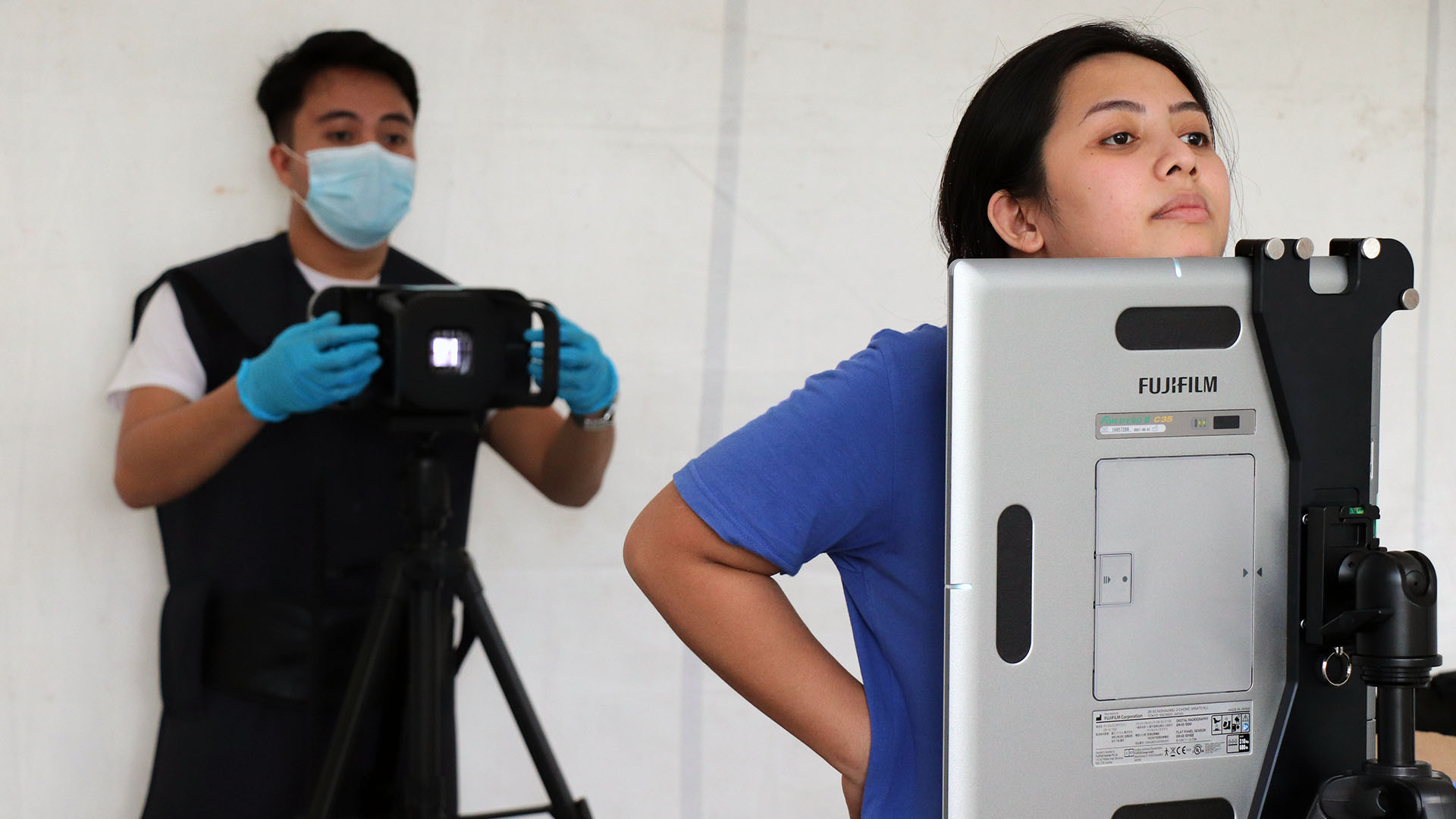

Baziwo, from Ibulanku sub-county, was trained by RHITES-EC. He tries to improve TB diagnosis and treatment by encouraging TB patients’ contacts and community members with TB-related symptoms to get screened and tested. He also supports patient follow-up and community sputum sample completion for patients that fail to return to the health facility upon completion of their TB treatment. He always carries a sputum container, gloves for infection prevention and control, and a notebook to record patient information.

“I call my patients before I go to their homes. They are surprised to hear from me, but I remind them that TB could restart in the body even after six months of treatment, or when they’ve stopped coughing, so I need to get another sample for testing,” Tadeo says.

Tadeo learned these best practices for proactive follow-up of TB patients at a virtual QI collaborative monthly meeting focused on TB patient monitoring, including those lost to follow-up.

Community-Based TB Testing Improves TB Cure Rates

Byobon and sub-county health workers such as Tadeo now follow up with all TB patients in Bugweri District, including TB patients who have completed treatment and require a six-month TB test to determine if they have been cured.

This community-level TB outreach best practice emerging from the TB QI collaboratives has made a difference in TB detection, treatment, and testing. The district TB cure rate increased from 35% in June 2020 to 86% in March 2021.