KI, a resident of Kisenyi, one of the largest slums in Kampala, had been out of touch with his family for several years. When he fell ill, he reached out to his sister, a health worker, who took him to Mengo Hospital, a private not-for profit hospital in Kampala, to be tested for TB.

At the hospital, KI was diagnosed with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis, a difficult strain of the disease to treat. The hospital transferred him to the nearest drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) treatment facility, Mulago National Referral Hospital.

URC’s USAID Defeat TB Project provides support to all the multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) treatment facilities in Uganda through direct service delivery and technical support to implement a comprehensive package for MDR-TB management including contact investigation. Defeat TB facilitates contact investigation by providing tracking tools, transport, and guidance on management of MDR-TB.

Once KI was admitted as a DR-TB patient, Mulago Hospital health workers quickly got to work to carry out contact tracing to evaluate his family and close contacts for active TB. Although a standard procedure in the management of DR-TB, in KI’s case, contact tracing would not be easy. Closed communities, such as Kisenyi, intentionally limit access and links with outsiders. But KI, concerned about the well-being of his friends, volunteered to take the health workers to his neighborhood.

The Mulago Hospital team was apprehensive to enter the slum where many residents were active drug users. KI accompanied the team and explained to his friends and other residents that he had been unwell, and that the health workers had taken good care of him. He told them why the team was there and urged them to take part in the screening. He was particularly concerned for his girlfriend whom he suspected was the source of his contagion. His suspicion was confirmed when her TB diagnosis came back positive.

Patient-led TB Contact Tracing Yields Results

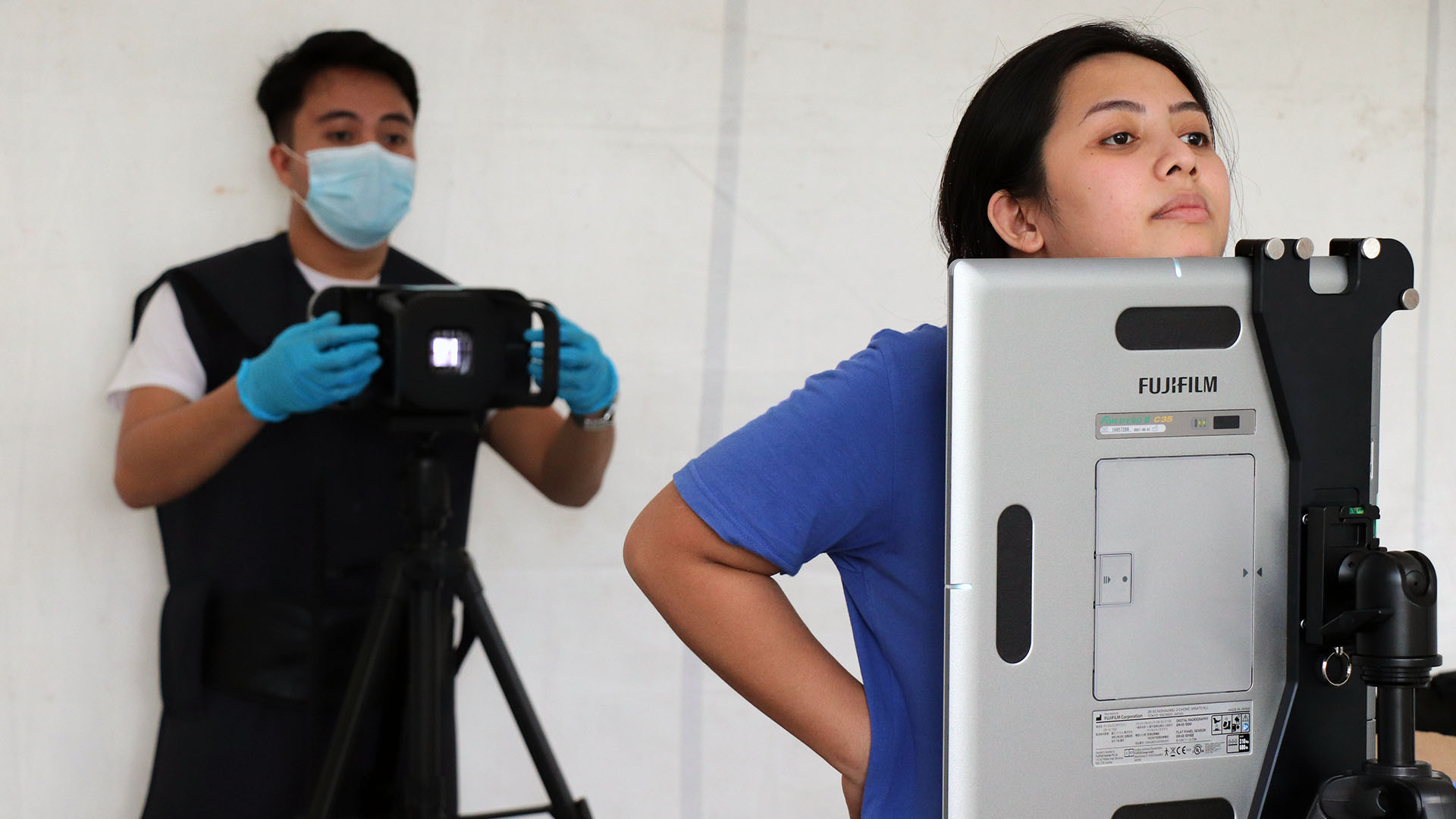

Forty of KI’s friends were screened for TB. Given the poor ventilation and congestion where many resided, all contacts with a current cough were presumed to have TB. Sputum samples from these presumed contacts were collected for GeneXpert testing. Six of the 30 presumed patients were diagnosed with TB which translates to a TB yield of 15%. This yield is five times higher than the 3% yield normally obtained through health worker-led contact tracing.

Because of KI’s connection to the community, health workers were able to organize and conduct TB screening in Kisenyi, a previously impenetrable area. KI allayed the fears and suspicions of residents explaining how the health workers had helped him get diagnosed and treated. The team succeeded in screening another 413 people in the community, of which 152 were presumed to have TB. Five of the 152 were diagnosed with TB using the GeneXpert machine.

The importance of community connections is key to obtaining access to closed communities for TB screening. Patient-led contact tracing can lead to a higher TB yield than the usual health worker-led approach. The approach enables health workers to access contacts of TB patients they would otherwise miss. Defeat TB will replicate this contact tracing approach for all TB patients who come from closed communities to increase TB case finding in these settings.