When people think about drug treatment, images of incarceration and mandatory inpatient treatment often come to mind. However, the understanding of drug use has changed in the past decade, and today, there is greater recognition that most users are low-to-moderate risk and can be treated without taking them away from their homes or work.

In fact, treatment must be available, accessible, and appropriate, according to the first principle of the “International Standards for the Treatment of Drug Use Disorders” by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime.

During the past decade, more countries have shifted toward community-based drug rehabilitation (CBDR). CBDR is a holistic process that incorporates prevention and health promotion, screening and assessment, drug treatment, wraparound family and community services, and aftercare programs closest to where people are.

In the Philippines, CBDR emerged in 2016 on the heels of the aggressive case finding that elicited more than 1.2 million potential clients. The Dangerous Drugs Board declared that a great majority of clients could be treated in their respective local government units (LGUs).

As the country had no history of CBDR, there was a lack of documentation on CBDR’s implementation and impact. To fill this gap, the URC-led USAID Expanding Access to Community-Based Drug Rehabilitation Program in the Philippines (USAID RenewHealth) project conducted case studies of 12 LGUs in the Philippines (seven in Metro Manila with five in Regions 4, 7, 8, and 10) to determine the costs, benefits, barriers, and enablers in implementing CBDR.

Barriers to and Enablers of CBDR

Common barriers to CBDR implementation are inadequate resources and limited facilities and equipment. Having dedicated funds for CBDR is important, and the results of the USAID RenewHealth case studies showed that LGUs invest anywhere from 0.04% to 0.53% of their annual budgets for CBDR activities.

The majority of LGUs do not have permanent CBDR staff and rely on volunteers to implement the program. However, some LGUs have hired full-time personnel to deliver or implement CBDR. The findings showed that ratios of CBDR staff members to clients ranged from 1:25 to 1:92, with an average ratio of one staff member to 45 clients.

An additional challenge cited was participant attrition due to conflicting schedules. A number of LGUs have addressed this concern by delivering CBDR programs on weekends or after work. LGUs also reported difficulties in obtaining the participation and cooperation of clients’ families. Key informants highlighted the importance of engaging the family.

Another barrier cited was community officials’ lack of cooperation. Not every official prioritizes CBDR and some still see drug use as a personal failure or don’t believe in rehabilitating drug offenders.

A key enabler cited by program managers was a strong service delivery network with collaboration between anti-drug abuse personnel, law enforcers, health workers, social workers, the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, and courts. Other LGUs cited the importance of having civil society and international partners as enablers for CBDR. For example, faith-based organizations and non-government organizations volunteer to help with CBDR programs.

CBDR Costs and Savings

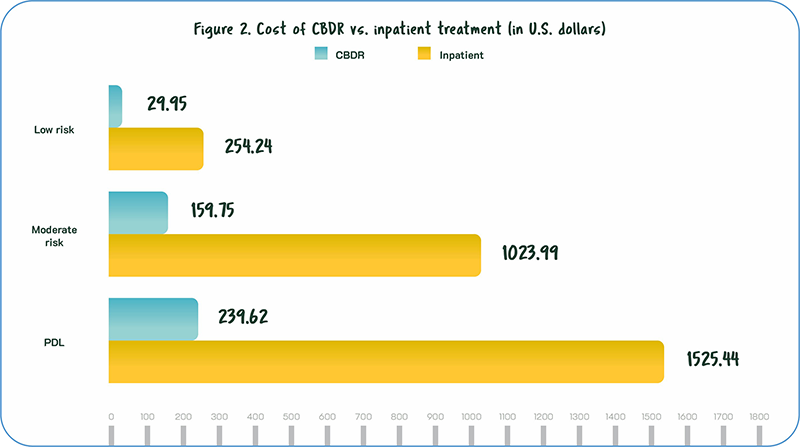

Overall, the USAID RenewHealth study found that CBDR provided great value in comparison to inpatient treatment in a government residential facility.

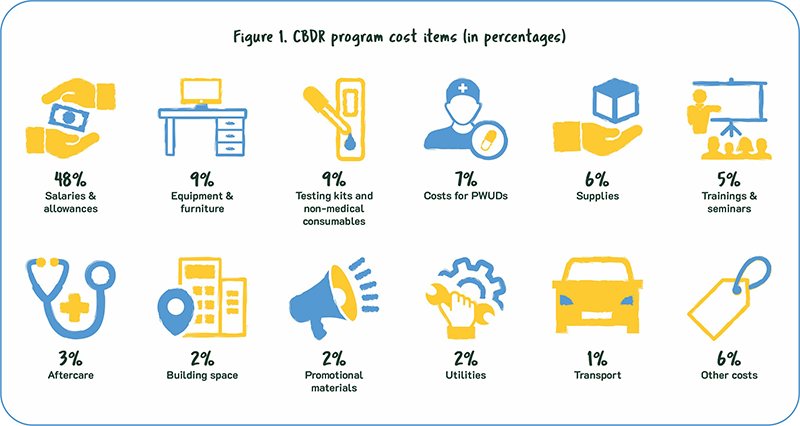

Human resources account for 48% of total CBDR program costs for all LGUs. The next highest expenses were testing kits, equipment, furniture, and supplies (see Figure 1). Other costs were for facility repairs and maintenance, meetings, other medical costs, training for program staff, and prevention programs in schools.

Even though CBDR requires funding, program managers recognized that its costs were relatively low compared to inpatient treatment. The cost of CBDR for low-risk clients was 12% of the cost of inpatient treatment. The cost of 15 CBDR sessions (for moderate-risk clients) was 16% of the cost of four months of inpatient treatment. And 24 CBDR sessions (for persons deprived of liberty) cost 16% of a six-month inpatient program. In general, the cost of inpatient treatment was 6-8 times the cost of CBDR (see Figure 2).

Positive Outcomes of CBDR

Beyond savings, both clients and program implementers shared a number of positive outcomes of CBDR. An LGU representative saw the program as providing a one-stop shop to support and address the clients’ needs and help them stop illicit drug use. He said, “Some clients want to stop but do not know how and where to start — the program opens an opportunity for them to act on their drug dependence.”

The positive impact was validated by Karding, a graduate of CBDR, who described her journey after becoming addicted to drugs.

“I lost my family and was imprisoned,” Karding said. “When I was released, I thought I could recover on my own. But I found myself still tempted to use. Our barangay suggested I attend, and I tried it. The facilitator was good, and I learned a lot from each of the 15 modules and took lessons to heart. I learned the bad effects of drugs, tips to avoid drug use, my triggers. I eventually was reconciled with my family and found a new job. CBDR was such a big part of my recovery.”

Service providers shared that their clients not only stopped drug use but also changed for the better. “Our clients now have a better outlook in life, are less irritable, and are less hot-headed,” one LGU representative said. “Before, they had frequent fights with their wives, but this has since been reduced.”

Other CBDR program successes reported by program managers and service providers included:

- Helping reunite and strengthen bonds within families. “The program helped a family member realize that it is not only the clients who have issues but there are other causes of drug use within the family,” said one service provider;

- Helping clients find employment and start small businesses;

- Addressing clients’ health needs through referral to health services and facilities; and

- Reducing stigma and discrimination in communities. “Without our CBDR program, clients will still feel ashamed and the community will still think they cannot change,” said one program manager.

Although CBDR is still in its infancy in the Philippines, the study emphasizes the importance of investing in and sustaining its implementation. The study has also shown how important it is to take a holistic approach to address the needs of PWUDs. The adage “it takes a village to raise a child” appears to be just as true for drug recovery.

“The general perception of a person who uses drugs is that they are mentally challenged and need to undergo rehabilitation in a facility. But not all of them needs to be ‘checked-in.’ Depending on the severity of drug use, some clients can stay home to their families and earn a living while eliminating drug use. CBDR gives them a chance to live.”

— Lito, CBDR program manager, National Capital Region

The shift to CBDR in Southeast Asia

Malaysia has transformed a third of its compulsory facilities into outpatient Cure and Care facilities.

In Cambodia, health centers provide CBDR; in Myanmar and Laos provide CBDR through district hospitals.

Vietnam provides voluntary treatment through community or home-based outpatient programs and methadone clinics.

Indonesia implements CBDR through nongovernmental organizations in community health centers, public hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and prisons.

In Thailand civil society organizations provide CBDR in temples and mosques.

Source: “Compulsory Drug Treatment and Rehabilitation in East and Southeast Asia,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2022).